Just look at those incredible astronomical images! They’re beautiful, awe-inspiring, breathtaking—words hardly seem enough to capture their wonder. But have you ever wondered how these stunning snapshots of the cosmos are made? Most people would think, ‘With a telescope, of course!’ And that’s true, but there’s more to it. How do we capture what we see? What turns those distant cosmic lights into images we can share and marvel at? There’s a powerful, often overlooked element behind these photos—’the detector.’ Detectors are the true magic behind the scenes, translating the faint signals from the universe into the images that leave us in awe.

The Eye as a Detector

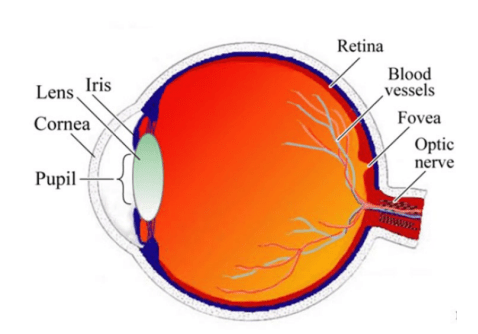

Before we dive into the cutting-edge technology of today, let’s take a step back in time. Did you know that every human has a miniature telescope built right in? Our eyes function much like a small telescope and detector combined. The pupil acts as an aperture, a lens refracts incoming light, and that light is then focused onto our retina, which serves as the detector. From there, the optic nerve sends signals to our brain, which processes these signals to create an image. This entire process relies on what we call ‘integration time’—the brief period, about a hundred milliseconds, during which our eye collects light before it sends the information to the brain.

However, our eyes aren’t perfect at capturing every detail. They are only sensitive to a narrow portion of the electromagnetic spectrum called visible light with peak sensitivity around 550 nm under daylight conditions. Additionally, they have low quantum efficiency, meaning they can only register only a few percentage of the photons (~3%) that hit the retina. The remaining simply doesn’t make it into our perception, which limits the clarity and depth of the images we see.

Until the 19th century, the human eye was the primary ‘detector’ astronomers had. They would observe the skies and carefully sketch what they saw. Galileo, for example, achieved incredible feats in astronomy by relying solely on his eyes and remarkable observation skills.

Photographic Plates

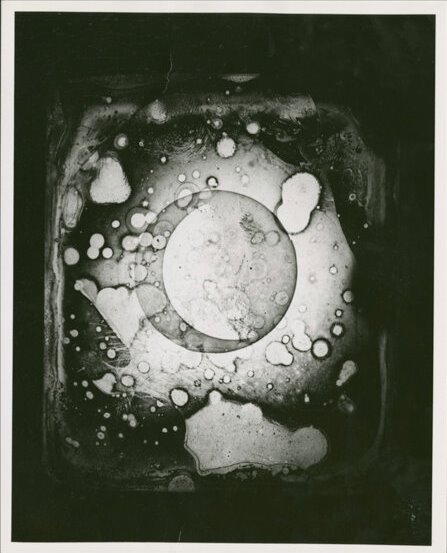

Then came the era of photographic plates, which revolutionized astronomical observation. The first known astrophotograph was taken in 1840 by John W. Draper using glass plates, which offered several significant advantages.

Firstly, photographic plates allowed for extended integration times, enabling astronomers to capture light from very faint celestial objects. This made it possible to image not only stars but also low-surface-brightness objects like nebulae. However, these plates also had notable limitations. The quantum efficiency of photographic plates was only a few percentage. However, it had a wider spectral response compared to human eye. Using photographic plates, capturing faint objects often required up to 10 hours of exposure. Additionally, telescopes needed to be perfectly stable for such prolonged exposures—any movement or error would mean starting the entire observation from scratch.

In 1840, John Draper’s pioneering daguerreotype of the Moon opened new horizons in Astrophotography, serving as a trailblazer for celestial imaging. Draper’s technique utilized a silver-plated copper sheet treated with iodine vapor to create a light-sensitive surface, capturing the Moon’s details with unprecedented clarity. This image was more than a photograph; it was a breakthrough that demonstrated photography’s potential to document and study celestial bodies with precision.

A further challenge was that photographic plates were single-use with no option for immediate backups. After each exposure, the plate had to be removed, carefully stored in climate-controlled vaults, and a fresh plate used for the next observation. This process was cumbersome and left little room for error. Moreover, photographic plates were only sensitive to visible wavelengths, restricting observations to a narrow portion of the spectrum depending on the emulsions used. Attempting to observe in wavelengths outside the visible range was impossible with this technology.

Another drawback was the non-linear response of these plates. Doubling the exposure time on an object did not result in a doubling of detected photons, making it challenging to accurately capture faint details. Lastly, these plates were fragile glass and prone to breaking, complicating storage and sharing—options that are much easier with today’s digital data. Despite these limitations, photographic plates marked a substantial step forward in astronomy, paving the way for modern imaging technology.

Greatest Of All Time – Charge Coupled Device (CCD)

The development of the Charge Coupled Device (CCD) in the late 20th century marked a breakthrough in astronomical imaging, often hailed as one of the greatest advances in observational astronomy. First invented in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Labs, CCDs transformed light into electronic signals with far greater sensitivity and efficiency than photographic plates, which were previously the standard in astronomy. The CCD technology isn’t just a powerhouse in professional astronomy; it’s a familiar part of everyday life, found in devices like our smartphones, digital cameras, and even computers. When you snap a picture with your phone, the CCD (or, in most modern cases, a similar CMOS sensor) captures incoming light and converts it into electronic signals to create a digital image. This works similarly to the way astronomers capture images of distant galaxies and nebulae. Just as a telescope’s CCD can detect faint light from stars.

CCDs allowed astronomers to capture and analyze faint celestial objects with remarkable precision, all while increasing quantum efficiency up to 90% (depending on the wavelength of light)—a monumental leap from very low efficiency of photographic plates. By the 1980s, CCDs had become an essential part of telescopic technology. For instance, in 1983, CCDs were installed on the 3.9-meter Anglo-Australian Telescope, which allowed astronomers to image distant galaxies and faint nebulae in greater detail than ever before. Later, in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) launched with CCDs at its heart, further pushing the boundaries of what could be observed. Hubble’s CCDs captured some of the most iconic images in astronomy, from detailed structures within the Eagle Nebula’s ‘Pillars of Creation’ to unprecedented views of deep field galaxies billions of light-years away. Dr. Nagaraja Naidu Bezawada, a detector engineer at European Southern Observatory (ESO), explains that “CCDs for Astronomy are designed to function optimally at temperatures between -100 and -120 degrees Celsius. Specialized instruments and electronics are used to regulate this temperature, with automatic adjustments in place to correct any detected drifting.”

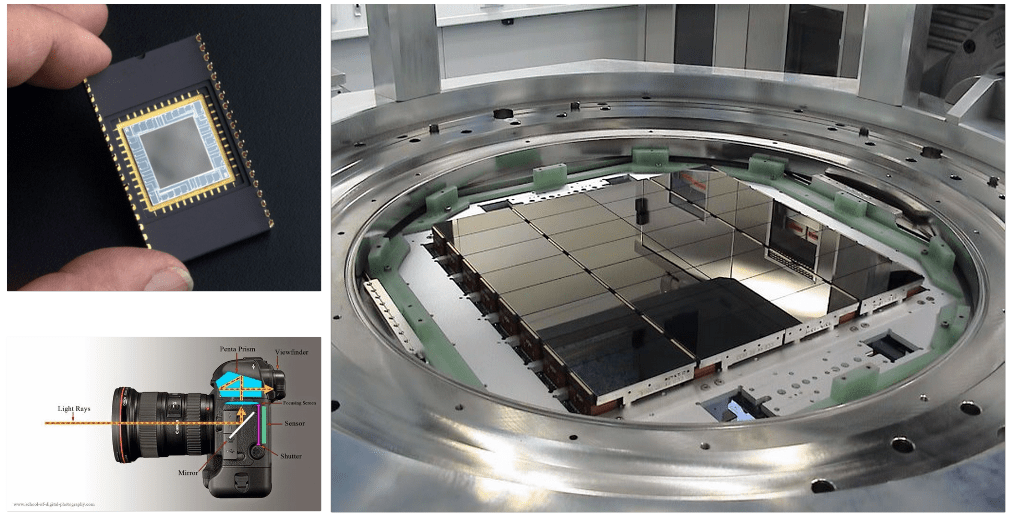

Right panel: 32 CCD detectors fitted in the OmegaCAM camera of VST that together create a detailed 268 megapixel images. Each detector measures about 6 cm by 3 cm.

Credit: ESO/INAF-VST/OmegaCAM/O. Iwert

Dr. Bezawada also explains, “Over the long term, contamination can occur, potentially degrading the Anti-Reflection (AR) coating of the CCD surface and leading to reduced performance. However, the silicon structure of the CCD remains stable due to its solid-state nature. In general, a CCD is expected to function effectively for 15-20 years.” However, performance is closely monitored for any signs of degradation, and when a CCD slowly degrades below acceptable performance, it is either replaced or upgraded with a better part as part of instrument upgrades. This ensures that observational capabilities remain efficient and uninterrupted.

In addition to revolutionizing visible-light imaging, CCDs also allowed for new possibilities in multi-wavelength astronomy. For example, CCD technology was adapted for X-ray observations on satellites like Chandra (launched in 1999), providing high-resolution images of high-energy phenomena such as black holes and supernova remnants. The adaptability, durability, and increased sensitivity of CCDs helped open up new wavelengths to study the universe, and their digital nature allowed images to be easily stored, processed, and shared. The impact of CCDs on astronomy has been so profound that Boyle and Smith were awarded one half of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2009, underscoring the CCD’s reputation as a game-changer. Today, CCDs remain foundational in astronomy, from ground-based observatories to space telescopes, making them truly one of the ‘Greatest of All Time’ technologies in the field.

Working mechanism of a CCD:

It is a simple process by which light from an object is captured by a Charge Coupled Device (CCD) sensor and transformed into an image. The CCD is made up of millions of tiny light-sensitive cells called pixels, which detect photons (light particles) and convert them into electrical signals. The same technology is used in both scientific instruments and everyday devices like phones, but there are some big differences in how each uses the CCD to capture an image and in how astronomers get color information. Dr. Nagaraja says, “The electronics and noise levels of the device needs be optimized. Faster readout speeds typically result in higher noise, so it is crucial to ensure that electronic noise does not overpower the intrinsic detector noise. To achieve this, both the electronics and the detector must be carefully optimized and calibrated to achieve required performance. Additionally, advancements in low-noise electronics and signal processing techniques are continually being developed to enhance the performance of CCDs.“

CCD Imaging:

CCDs in phones have color filters (often a Bayer filter) over each pixel in red, green, or blue (RGB), allowing the sensor to capture color information. By combining data from these filtered pixels, the phone’s processor builds a full-color image. Phone CCDs are also designed for fast, automatic settings to capture images quickly in everyday lighting conditions. Telescopes, especially those used in professional astronomy, have much larger and more sensitive CCD sensors. Unlike a phone, a telescope CCD often captures images over a longer exposure time, meaning it can keep gathering light from very faint objects for minutes, hours, or even longer. This longer integration time allows telescopes to capture incredibly faint light from distant stars, galaxies, and nebulae that would otherwise be invisible. Hence, the CCDs in astronomical instruments are cooled to -100 to -120 degree Celsius to reduce the inherent dark signal to negligible levels such that the celestial objects can be imaged with high signal to noise ratio which results in better quality of the image.

Unlike phone sensors, telescope CCDs do not typically use color filters on the sensor itself. Instead, astronomers use separate filters—often mounted on a filter wheel—that filter the incoming light into specific colors or wavelengths (like red, green, blue, or even specific narrowband wavelengths like hydrogen-alpha, which emits in red). By taking multiple images through these different filters, astronomers can gather detailed color information and then combine the images to produce a full-color picture.

To get color images of galaxies or other celestial objects, astronomers usually follow a multi-step process:

- Capturing Separate Filtered Images:

- Red, Green, and Blue Filters: Similar to how our eyes perceive color, astronomers use red, green, and blue filters in their instruments. They take separate images of the same object through each filter. For example, they’ll take a “red” image (only red light passes through), a “green” image, and a “blue” image.

- Narrowband Filters: For even more detail, astronomers might use narrowband filters that capture specific wavelengths, like hydrogen-alpha (red) or oxygen-III (green-blue), which highlight specific gases. This is especially useful in nebulae or regions where certain elements emit distinct wavelengths of light.

- Combining Filtered Images:

- After capturing images through different filters, astronomers overlay and combine them to create a full-color image. The red-filtered image contributes red tones, the green-filtered image provides green tones, and the blue-filtered image adds blue tones to the final picture.

- In some cases, astronomers assign colors to specific wavelengths that fall outside the visible spectrum, creating “false-color” images. For instance, they might map infrared or ultraviolet light to visible colors to highlight specific features, like hot young stars or cool gas clouds.

- Post-Processing and Color Adjustment:

- Finally, astronomers adjust brightness, contrast, and color balance to bring out details that may be subtle in the raw data. They aim to represent the colors accurately, but sometimes adjustments are necessary to make the details more visible. This processed image is what we often see in beautiful space photos, where galaxies glow with a mix of colors representing their stars, gas, and other features.

CCD Spectroscopy:

CCDs are also very commonly used in Spectroscopy, where they play a crucial role in capturing spectra, the detailed breakdown of light by wavelength, from celestial objects.In spectroscopic applications, CCDs don’t capture an image in the traditional sense but rather record the distribution of light intensities across different wavelengths which reveals information about the object’s composition, temperature, motion, and more.

Dispersing Light: Light from the astronomical object (such as a star, galaxy, or planet) is collected by a telescope and passed through a spectrograph, an instrument with a dispersive element like a prism or diffraction grating. This component splits the light into its component wavelengths (like a rainbow).

Recording the Spectrum with a CCD: The dispersed light then falls onto a CCD, where each wavelength is focused on a different parts of CCD. The CCD records the brightness of each wavelength, creating a graph-like image, or “spectrum,” of light intensity versus wavelength.

Extracting and Analyzing the Spectrum: Astronomers analyze this spectral data to understand properties of the object, such as:

- Composition: Different elements emit or absorb light at specific wavelengths, so each element has a unique spectral “fingerprint.” By examining the spectrum, astronomers can determine what elements are present.

- Temperature: The shape and intensity of a spectrum can reveal the temperature of the emitting material.

- Velocity: By measuring shifts in spectral lines (Doppler shifts), astronomers can determine the speed at which an object is moving towards or away from us.

- Density and Physical Conditions: Other spectral features can indicate physical conditions like pressure, density, and magnetic field strength.

CCDs are Ideal for Spectroscopy

CCDs are highly sensitive and can detect faint signals, making them well-suited for gathering light over a wide range of wavelengths, from visible to infrared. They also have high quantum efficiency (the ability to convert incoming photons into electrical signals), which is essential for capturing detailed spectra even from distant or faint sources. Additionally, CCDs themselves do not provide digital data, but the CCD camera system (CCD + controller electronics and acquisition software), making it easy to analyze and process the spectral information using computers.

Example Applications of CCDs in Spectroscopy

- Stellar Spectroscopy: CCDs are used to study the spectra of stars to classify them, determine their chemical composition, and understand their evolutionary stage. For example, the 10-meter Keck telescopes in Hawaii use CCDs with spectrographs like the HIRES (High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer) to study stellar spectra at high resolution.

- Exoplanet Atmospheres: The Hubble Space Telescope uses CCDs in the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) to capture spectra of light that passes through an exoplanet’s atmosphere as it transits its host star. This can reveal the presence of molecules like water vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide, giving insight into the planet’s potential habitability.

- Galaxy Spectroscopy: CCDs are used to study distant galaxies’ spectra to learn about their chemical composition, star formation rates, and movements within the universe. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) uses CCD-equipped spectrographs to gather spectral data from millions of galaxies.

CMOS vs CCD:

Despite their enduring utility, the potential replacement of CCDs with CMOS detectors is a topic of active discussion. CMOS detectors offer advantages such as lower power consumption and faster readout times, but CCDs currently retain an edge in sensitivity and noise performance in certain applications.

Types of CCDs:

There are quite a few types of CCDs that has unique characteristics suitable for specific research case across various telescopes.

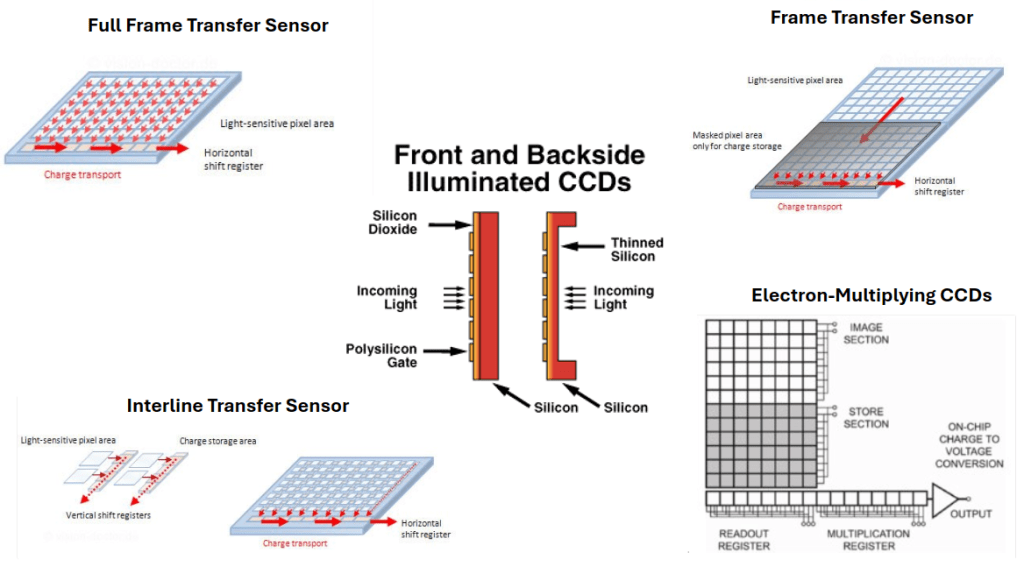

1. Back-Illuminated CCDs

Back-illuminated CCDs are sensors where the light-sensitive surface is on the back of the chip, eliminating obstructions from wiring and circuitry that are present in front-illuminated CCDs. Almost all astronomical CCDs are back-illuminated. Almost all CCDs in general are back-illuminated.

Research Case: Ultraviolet and optical spectroscopy for exoplanetary atmosphere studies.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: Hubble Space Telescope (HST) with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS).

2. Front-illuminated CCDs

A front-illuminated CCD is a type of sensor where light enters from the same side as the electrode structure. These CCDs are less frequently used than back-illuminated mainly due to their low quantum efficiency.

Research case: Front-illuminated CCDs have been effectively used in solar astronomy and laboratory-based plasma experiments, where targets are very bright and low dark current or ultra-high sensitivity isn’t critical.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: The STELLA telescopes (located in Tenerife, Canary Islands) use front-illuminated Teledyne e2v CCDs in their imaging and spectroscopy instruments. These are used for robotic monitoring of bright stars, exoplanet transits, and stellar activity, where the photon flux is high, and dark current suppression is less crucial.

3. Full-Frame CCDs

A full-frame CCD is a back-illuminated CCD type of charge-coupled device where the entire surface of the sensor is used to capture light. – full frame are back-illuminated CCDs

Research Case: Deep-sky surveys and high-resolution galaxy imaging.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: Subaru Telescope, an 8.2-meter optical-infrared telescope located on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

4. Frame-Transfer CCDs

Frame-transfer CCDs are back-illuminated and can quickly shift the entire image from the light-sensitive area to a shielded storage area before readout, enabling rapid image capture without a shutter.

Research Case: Time-sensitive observations of transient events like supernovae or variable stars.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: The 2.5-meter Isaac Newton Telescope (INT) located at La Palma, Canary Islands.

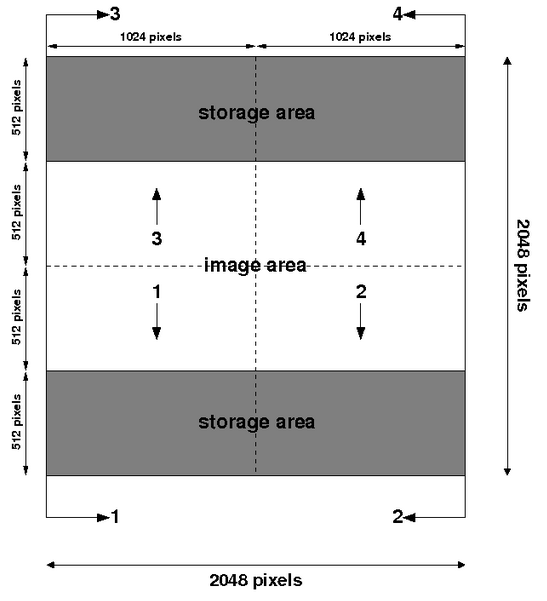

- Split Frame transfer device:

- These are specialized variant of frame-transfer CCDs, optimized for ultra-fast imaging by splitting the chip into two image areas, each with its own adjacent storage region—typically above and below the central imaging area. This configuration allows for simultaneous exposure and readout processes. While one half of the CCD is capturing a new image, the other half is reading out the previously captured data. This overlapping operation significantly reduces dead time between exposures, enabling the capture of rapid sequences without the need for a mechanical shutter.

- Research Case: This structure is especially useful in time-domain astronomy, where capturing rapid changes (like pulsations, eclipses, or flares) with minimal delay between exposures is essential.

- An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: 10.4-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC), located at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma, Canary Islands.

- These are specialized variant of frame-transfer CCDs, optimized for ultra-fast imaging by splitting the chip into two image areas, each with its own adjacent storage region—typically above and below the central imaging area. This configuration allows for simultaneous exposure and readout processes. While one half of the CCD is capturing a new image, the other half is reading out the previously captured data. This overlapping operation significantly reduces dead time between exposures, enabling the capture of rapid sequences without the need for a mechanical shutter.

5. Electron-Multiplying CCDs (EMCCDs)

This Back-illuminated CCD amplifies the signal generated by incoming photons before readout, enabling the detection of extremely faint light levels by effectively multiplying the number of electrons.

Research Case: Low-light spectroscopy of faint celestial objects, like distant galaxies or faint stars.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing This CCD: The Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) on La Palma, Canary Islands, with the OSIRIS instrument (Optical System for Imaging and low-Intermediate-Resolution Integrated Spectroscopy).

6. Interline Transfer CCDs

This front-illuminated CCD can transfer charge from light-sensitive pixels to adjacent shielded pixels for quick image capture. This is an older version where spatial resolution was reduced due to the storage area occupying part of each pixel—so they might not be used for applications requiring high sensitivity or fine spatial detail, such as deep-sky astrophotography. While not typically used in faint-object astronomy due to lower sensitivity, their ability to quickly capture clear, smear-free images makes them invaluable in environments where timing and motion are key factors.

Research Case: Planetary imaging and studies of fast-moving objects in our solar system.

An Example of the Telescope Utilizing this CCD: NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) with its HiRISE (High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) camera.

Advantages of CCD:

- High Sensitivity

- Broad Wavelength Range

- High Image quality and resolution

- High linearity and uniformity

- Long Exposure time

- Stable and Reliable

Disadvantages of CCD:

With a big revolution of a new technology also comes with a few disadvantages.

- Expensive Production:

- CCDs are relatively expensive to manufacture, particularly large, high-resolution, and high-sensitivity CCDs used in professional astronomy. Specialized CCDs, like back-illuminated and EMCCDs, are even more costly.

- Cooling Requirements:

- CCDs generate thermal noise (or dark signals), which can affect image quality, especially during long exposures. To reduce this noise, they often require cooling systems, sometimes down to cryogenic temperatures. This adds complexity, bulk, and power requirements to CCD-based systems.

- Slow Readout Times:

- Compared to CMOS sensors (commonly used in consumer devices), CCDs have slower readout times, which can limit their use in applications requiring high-speed imaging. The readout process also consumes more power.

- Blooming Effect:

- When bright light saturates a CCD pixel, it can cause charge to “spill over” into adjacent pixels, creating streaks or blooming artifacts in the image. Anti-blooming technology can mitigate this issue but at the cost of some sensitivity.

- Lower Radiation Tolerance:

- CCDs are susceptible to damage from high-energy particles and radiation, especially in space applications. Over time, exposure to radiation can degrade their sensitivity, necessitating special shielding or regular calibration.

When asked about his most memorable experience as a detector engineer, Dr. Bezawada shares, “The Flame Nebula—it’s one of the images captured using the VIRCAM, in which I was a part of the team that built the camera in infrared light with the VISTA telescope.” He elaborates that this image highlights the intricate details of the nebula, which are invisible in optical wavelengths but beautifully revealed in the infrared spectrum. This accomplishment not only showcases the capabilities of modern detectors but also underscores the importance of advanced instrumentation in unveiling the hidden wonders of the Universe.

Credit: ESO/J. Emerson/VISTA

References:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjEoQt9OUis

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8JIB_Ona60

- https://www.eso.org/public/germany/videos/eso0949l/?lang

- https://www.eso.org/public/austria/images/eso0949n/

- https://www.eso.org/public/videos/cs0014a/

- https://vikdhillon.staff.shef.ac.uk/hipercam/info.html#optics

- https://www.teledynespaceimaging.com/en-us/applications/ground-astronomy