For a long time, we’ve been thinking that rainforests, especially the Amazon, are the ‘Lungs of the Earth.’ It’s a beautiful idea, because everywhere you look there’s so much life and greenery. But if you look at the actual numbers, the real source of most of Earth’s oxygen isn’t the forests at all, it’s the OCEAN – the true oxygen queen of our planet.

The truth is that the ocean produces a staggering 50 to 80% of the oxygen in our atmosphere. This incredible, planet-sustaining feat isn’t performed by giant kelp, but by an microscopic army called phytoplankton. These single-celled organisms, invisible to the naked eye, includes marine algae and cyanobacteria that tirelessly perform photosynthesis across the sunlit surface waters. The tiny species Prochlorococcus: the smallest photosynthetic organism on Earth, yet it alone produces up to 20% of all the oxygen in our biosphere, more than all the tropical rainforests combined!

The Birth of the Blue

To truly appreciate this invisible army, we must first look at the stage they inhabit. Long before life took hold, Earth had to acquire its oceans. While the theory for the origin of water remains complex (involving comets, asteroids, and water vapor released from volcanic rock), the formation of the ocean basins themselves is a grand story of geology. They are the result of plate tectonics, where the constant, slow-motion movement of continental and oceanic plates creates the deep depressions where water has collected for eons.

The Dawn of the Oxygen Revolution

For the first half of its 4.5 billion-year history, Earth was an alien world: a watery planet that was almost entirely anoxic (oxygen-free). Life arose 3.7 billion years ago, but these early microbes were anaerobic, getting their energy from chemicals like sulfur or by producing methane. The great mystery is: what powered life’s first world-changing invention?

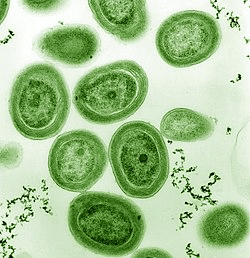

The answer lies with the cyanobacteria. Evolving around 3.5 billion years ago, these simple organisms performed an extraordinary feat: oxygenic photosynthesis. This process uses light to split water, releasing oxygen as a toxic byproduct.

Over the next billion years, the oxygen they produced served as a planetary cleaning agent. It first rusted the entire global ocean by oxidizing vast amounts of dissolved iron, creating the massive geological signatures known as banded iron formations. Once this oceanic “sink” was filled, the oxygen finally spilled into the air, leading to the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) approximately 2.4 billion years ago: the moment our planet took its first breath of air.

The Science of the Queen’s Army: Phytoplankton

The vast majority of oxygen production comes from the tireless work of phytoplankton, the microscopic algae and cyanobacteria that populate the sunlit photic zone (the top layer of the ocean where light penetrates).

The science behind their work is photosynthesis, specifically carried out within specialized structures called chloroplasts (which originated from ancient, symbiotic cyanobacteria). The reaction is elegant and essential:

Carbon Dioxide + Water + Light Energy → Sugar + Oxygen

6CO2 + 6H2O + Light → C6H12O6 + 6O2

Phytoplankton, like the dominant bacterium Prochlorococcus, are primary producers that anchor the marine food web. They consume carbon dioxide, making them critical in regulating Earth’s climate, and release oxygen as a life-sustaining byproduct.

The Deep Mystery: Oxygen from Rocks in the Abyss

We usually think of sunlight as essential for oxygen production. Yet, in 2024, scientists uncovered something extraordinary: rocky lumps lying 4,000 meters beneath the pacific ocean, far beyond the reach of light, are capable of generating ‘dark oxygen.’ Isn’t that fascinating? This oxygen is not created by life, but by geology. These metal-rich rocky lumps on the seafloor, known as polymetallic nodules (rich in manganese, nickel, and cobalt), can generate an electrical charge, effectively acting as “geo-batteries.”

The concept works through a process called seawater electrolysis. The electrochemical potential generated by the nodules’ metallic composition is high enough to split the surrounding water molecules (H2O) into hydrogen gas (H2) and oxygen gas (O2). This challenges the long-held assumption that all oxygen in the deep ocean must be supplied by slow diffusion and circulation from the surface. While the amount of “dark oxygen” is small, this localized production provides a potential oxygen source that supports microbial life and tiny organisms in an environment previously thought to be completely reliant on oxygen from above. The result of this study were published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The Silent Suffocation: Global Warming and Ocean Oxygen

While, the ocean’s role as the Earth’s primary oxygen producer, it is critically threatened by global warming, a process known as ocean deoxygenation. This occurs due to two major, interconnected effects:

- Reduced Solubility: Warmer water simply holds less dissolved gas, including oxygen. As the ocean absorbs over 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases, the surface waters become less capable of dissolving and holding oxygen from the atmosphere.

- Increased Stratification: Warmer surface water is less dense and therefore more buoyant than the colder water beneath it. This density difference severely limits the mixing (or circulation) of oxygen-rich surface water with the deeper layers.

Statistical Evidence:

- Globally, the oceans have already lost about 2% of their dissolved oxygen since the 1960s. By 2080, a 2021 study reported, more than 70 percent of the global oceans will experience noticeable deoxygenation.

- Areas of extremely low oxygen (called Oxygen Minimum Zones or OMZs) have been expanding. The volume of anoxic ocean waters, areas completely depleted of oxygen has quadrupled since the 1960s.

- The largest oxygen loss is concentrated in the upper 1000 meters which is the most species-rich part of the water column.

This decline is not just a statistical curiosity; it forces marine life, including sensitive fish species, to move into smaller, shallower ranges, increasing competition and decreasing biodiversity.

What can be done? To reduce ocean deoxygenation, the most critical actions are directly addressing its two main human-caused drivers:

- Global warming: Reducing green house gas (CO2) emission by switching to renewable energy; restoring the blue carbon ecosystem (mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes).

- Nutrient pollution: In coastal areas, the primary cause of oxygen depletion (hypoxia or “dead zones”) is eutrophication. When too much fertilizer (which is full of nutrients) and sewage runs off the land and reaches the coast, it causes a huge, rapid growth of algae, called a bloom. When all this extra algae dies, bacteria eat it up, and in the process, they use up almost all the oxygen in the water. To fix this, farmers can use less fertilizer by using methods like precision agriculture (only applying what’s needed), planting cover crops (to keep soil and nutrients from washing away), and planting natural buffers along streams to filter out the pollution before it reaches the sea.

Ocean Worlds and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

The fact that water (H2O) is indispensable for all known life on Earth explains why it is the “gold standard” in the astronomical search for life. Astronomers are intensely focused on oceanic planets and moons to search for life inside and outside our solar system.

Key Targets in our Solar System:

- Europa (Jupiter’s moon): Possesses a massive saltwater ocean beneath its icy crust, heated by tidal forces from Jupiter.

- Enceladus (Saturn’s moon): Vents plumes of water vapor and organic molecules into space from its subsurface ocean, providing accessible samples for study.

- Titan (Saturn’s moon): Has surface lakes of liquid methane and a subsurface water ocean.

The search for life beyond our solar system hinges on finding liquid water, and that focus has led to the discovery of several fascinating exoplanets that exemplify the possibility of ocean worlds:

1. K2-18 b: The Hycean Candidate

- Type: Sub-Neptune or Super-Earth (larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune).

- Significance: K2-18 b, located about 124 light-years away, orbits its cool M-dwarf star within the habitable zone, meaning the temperature range is right for liquid water. Observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have detected carbon-bearing molecules like methane and carbon dioxide in its atmosphere, along with a shortage of ammonia. This atmospheric chemistry strongly suggests it could be a Hycean exoplanet, a world theorized to have a hydrogen-rich atmosphere enveloping a vast, deep water ocean. Intriguingly, initial JWST data also provided a possible detection of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a molecule that, on Earth, is primarily produced by marine life (phytoplankton!), making this one of the most compelling targets for studying biosignatures.

2. TRAPPIST-1e: The Rocky, Temperate World

- Type: Terrestrial (rocky) exoplanet, slightly smaller than Earth.

- Significance: TRAPPIST-1 is a system of seven rocky, Earth-sized planets orbiting an ultracool dwarf star (a star much dimmer than our Sun). Three of these planets are located firmly within the habitable zone, with TRAPPIST-1e being one of the most promising. Its density is consistent with a rocky composition, and it receives enough stellar energy to potentially maintain liquid water on its surface. While the TRAPPIST-1 star is active (emitting frequent flares), the planet’s characteristics: its size, its temperature profile, and its likely rockiness making it a prime analog for a temperate, water-bearing world.

3. LHS 1140 b: The “Super-Earth” with a Deep Ocean

- Type: Super-Earth (about 1.7 times the size of Earth).

- Significance: This planet orbits an M-dwarf star located about 41 light-years away. LHS 1140 b is notable for being in the habitable zone and having a relatively dense, potentially massive atmosphere that could shield it from the star’s stellar activity. Crucially, its overall density, calculated from its mass and radius, is consistent with models suggesting it may be a true ocean world, where a significant fraction of its mass perhaps even a majority is composed of water. It represents a potential model for exoplanets that formed in water-rich regions and hold their liquid water beneath a thick atmosphere.

These examples underscore the primary directive of astrobiology: where there is liquid water, there is a chance for life, whether that water is on the surface, beneath an icy crust, or beneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Expected Life Forms:

On these cold, dark, high-pressure subsurface oceans, we are absolutely not expecting whales or dolphins. Instead, astronomers and astrobiologists expect life to resemble Earth’s most resilient and primitive organisms: microorganisms similar to Earth’s extremophiles.

This expected life would likely be chemosynthetic, meaning it would draw energy not from the sun, but from chemical reactions at hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, similar to the ecosystems found in Earth’s deep trenches. These organisms would likely be simple, single-celled microbes (bacteria or archaea) that metabolize chemical compounds like hydrogen, methane, or sulfur to drive their life processes, confirming that life can thrive in the complete absence of sunlight.

Life is less of a miracle and more of a universal inevitability !